The Alchemy of the Renaissance

- Eli Stephens

- Jan 5, 2024

- 5 min read

The French poet Alain de Lille said, “A thousand roads lead a man forever to Rome.” This was his observation of the European world in 1175, during the height of the Middle Ages. The meaning then was obvious, His Holiness the Pope, at the time of Alain de Lille was Pope Alexander III, sat in Rome and controlled most of European Christendom. There in Rome, the capital of a ruined Empire, all of Europe’s powers looked for leadership. But many in Rome found their eyes wandering from the Holy See to the ruins surrounding it as the Holy See itself became divided. This, along with clashing kingdoms and another declining empire, brought an end to the Middle Ages and planted the seed for the Renaissance.

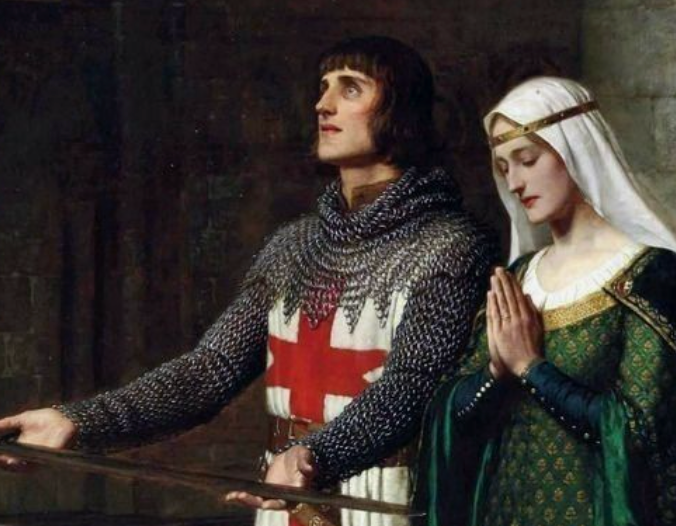

The best date to begin is 1303 A.D. with the context of the Babylonian Captivity in France. King Philip IV, after finding himself at the end of major political pressure from Pope Boniface VIII, takes one of the most major actions during the period, an arrest of a Pope. After adjourning a council of cardinals and high-ranking nobility, King Philip orders the arrest of Boniface to stand trial for his overreach over divinely appointed crowns. Boniface was, in fact, arrested by Philip’s men, but after a mob of commoners rushed towards the small group of warriors, they were forced to release Boniface and retreat back to France. (Lerner, 1968) Boniface immediately went back to Rome, but died a month later, bringing in Pope Benedict XI. Benedict, though, only lived for eight months as Pope before dying in what contemporaries of the event called suspicious circumstances. With Benedict’s death, Philip had the opportunity to oversee the election of Pope Clement V, giving him immense power in Europe. (Encyclopaedia, Clement V, 2023) In Philip’s reign, France became independent from the collapsing Holy Roman Empire, he completely eradicated the Knights Templar, one of the oldest Christian orders in the world, and won major wars with Flanders and brought peace with England, all by placing the Papacy seat in Avignon in 1309 A.D.. (Brown, 2023)

This brings us into the life of Petrarch. Born in 1304 A.D., he had firsthand experience of the turmoil during this period. His father had been employed by Pope Clement V, forcing the family to move to Avignon where Petrarch spent his childhood. Very quickly, Petrarch felt a great cynicism for his society. With his father being a notary, both Petrarch and his brother were expected to become students in the field. He would finish his studies in law, but would never work in it because he said, “I couldn't face making a merchandise of my mind.” (Plumb, 1985) To him, the justice system of the time had already become so corrupted that he could no longer participate. Instead, he focused closely on being a scholar and developing a strong network of friends with greats like Guido Sette and Giovanni Boccaccio. There, all of them engaged in deep dialogues about the history of their home, Italy. As this network of scholars begins, the macro politics of the region grows much worse in Petrarch’s life. The Black Death entered Europe, killing off many of Petrarch’s close friends, also France and England began their Hundred Years War, and soon almost every Papal election became extremely contested as the Papal seat itself lost its prestige. Petrarch, a religious man and lover of God’s virtues, finds himself becoming more and more disillusioned by his time’s landscape. This forces him to go on a pilgrimage back to Rome as everything collapses around him. Here, he renounced sensual pleasures and focused on his travels and studies. (Encyclopaedia, 2023) This is where one of the major ingredients of the Renaissance begins.

While in Rome, he finds another like-minded individual by the name of Cola di Rienzo who is openly advocating for the end of a monarchy in Rome and a return to the Ancient Roman Republican model of governance. Petrarch becomes a prominent supporter of this as he is also translating a certain set of letters he discovered in Verona five years prior to entering Rome. Inside them is correspondence from Ancient Roman Statesman Cicero to Atticus, Quintus, and Brutus, his close friends and colleagues. Through the letters, Cicero gives his personal thoughts and beliefs on his day’s topics and politics, saturating all of his letters with Classical thinking. With an already fertile landscape from the brewing chaos, Petrarch’s discovery and translations of these letters let the Renaissance take root in Christendom. Christian Humanism quickly spreads throughout clergy and theologians as Petrarch becomes a true participant in the Church. Soon Cola di Rienzo’s beliefs of the Roman Republic flourished throughout Italy. Still, a few more decades must pass and one of the most hectic events of the Middle Ages must occur before the Renaissance can truly blossom: The Western Schism.

Petrarch died in 1374 A.D. Four years before the madness of the Western Schism began, his work was quickly entering scholarly circulation amongst all the universities in Europe. Rome’s longings to return to its greatness are so palpable that in 1378 A.DThe election of a new Pope came after the death of Pope Gregory XI. Gregory had attempted to return to Rome and take back the city for the Papacy but found so much turmoil that he could only try returning to Avignon, but died before he could. Thus, the seat of the Papacy is open again. The Cardinals elect Urban VI after a massive outcry from Roman citizenry forced their hand to elect an Italian archbishop. Politics quickly reentered the Vatican as French Cardinals made protests. Urban VI gave them no quarter, making them conspire to elect their own Pope within their separate College of Cardinals. In this college, Clement VII was elected. Immediately, entire kingdoms chose sides, saints were pitted against saints, and universities dove back into their studies for solutions. One proposal from the University of Paris was swiftly rejected as it called for both the Pope’s (Boniface IX) and Antipopes (Benedict XIII) successors to resign so a new one could be elected. (Logan, 2002) Eventually, both lines agreed to end their successions at the same time, but no one followed the pacts, so a Pisan council was made by many enraged cardinals to elect a third Pope.

With such a massive power struggle occurring, many Italian scholastics found themselves as cynical as Petrarch. Soon, local politics became more important than world politics, creating the first lines of the many banking families that would rule Italian city-states. Petrarch’s writings reach the artists and philosophers who quickly take them to heart as the Church’s apparent collapse continues. Meanwhile, Cola Di Rienzo’s dreams of the Roman Republic became mainstream. Soon Florence threw out the Holy Roman Emperor’s vassal and regained the city’s Republican status. Armies of noble knights devoted to the Lord had already been destroyed by Philip IV, so quickly mercenary bands began roaming the Italian countryside. Intense competition called for improvements to technology and culture as the Middle Ages finally reached an end with the election of Pope Martin V in 1417 A.D.. However, he would not return to Rome until 1420 A.D. since the city and the Papal States had been plunged into chaos. The papacy found itself with many new challenges caused by the revival of classical ideals. Eventually, a short peace would return to Europe, but it would again be undone by the Protestant Reformation, the continuation of the Papacy’s waning position in Europe.

Petrarch, King Philip IV, three Popes, and Cicero: the main ingredients of the Renaissance. Once King Philip IV set the backdrop for Petrarch’s circumstances, it was only natural he’d find Cicero’s letters as he hid himself away from the madness of his time. Then once the Western Schism arrives, Petrarch’s classicalism can only flourish from there as the once ruling authority in Europe loses its trust in the general populace and the ruling class, bringing an end to the Middle Ages.